Research in Practice

by Clare Nisbet

#autoethnography #space #event #memory #ethnography #imagination #self #housing estate #home #archive #community #daydream #nostaglia #imagination

My Practice as an artist draws upon my professional experience as an architect and enables me to deal with specific areas of interest on the topics of spatial practice, narratives, home culture and identity. This research study seeks to take architectural/artistic theories of spatial practice combined with the notion of embodied memory as a framework to investigate the childhood memories of a first home on a mid century built housing estate in Leicester.

An autoethnographic study, the research was conducted in a physical locality, through a mixed method of data collection to identify specific locations of remembered places and events. By combining the freshly collected information in the present, by way of presented photographic and artistic productions, it is hoped that the act of reflecting on the past, with a critique of the situatedness of self with others and recalling memories can take on a re-evaluation. It is hoped that knowledge of one person’s perspective on the theme of memory and culture, can give new insight and appreciation of the present lives of others by connecting the past in todays world.

CONTENT

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Memory, Nostaglia and Images – snapshots of a time

4. Spaces, events and embodied memories

5. Conclusion

6. References

This archival and auto ethnographical study is a personal study of the memories of spaces from home life in early childhood. The attempt is to revisit spaces in order to gain an understanding why spaces, events, memories are important to us and are more than just what they are in reality. What is the comparison between these spaces from the past and now ? How do our emotions affect our memories and connections to places, people and objects ? The study is a narrative from a certain time, in a certain place.

Is it possible to learn more about today’s home culture by revisiting memories from our early domestic childhood? Can we learn more about today’s society through revisiting, visualizing spaces, objects and memories within our domestic environments to rethink our present and future?

These questions currently seem too huge to be answered by research alone, and need to be narrowed to a specific topic. The research therefore takes a specific place and time in history and to take a creative approach forward to possibly identify these questions.

The aim of this research study is to look in more closely at these hopes, dreams and fears of the post war period against a world today. By making these comparisons alone we are comparing the past with now – even though we acknowledge and know we live in different times. Identifying the cultural and political ideologies of that time is pertinent with resonances with of our current world.

Taking these contemporary similarities, my exploration is to take places or spaces and re-discover their meaning, through our eyes now and the eyes of our memories in relation to the production of space. To delve deeper into this research, my reading has taken me to associated areas – how our memories work, how is the subject of nostalgia seen nowadays ? and what part do day-dreams take in conjunction with memories ?.

To begin, the practice methodology is discussed to identify it’s suitability to this study and how this research is conducted. Autoethnography is a relatively new methodology, which raises ethical questions and has been criticized for it’s self indulgent approach (Griffin S&M (2019). It is important to identify how the autoethnographic approach is taken in connection with this research and the methodology addressing this subject.

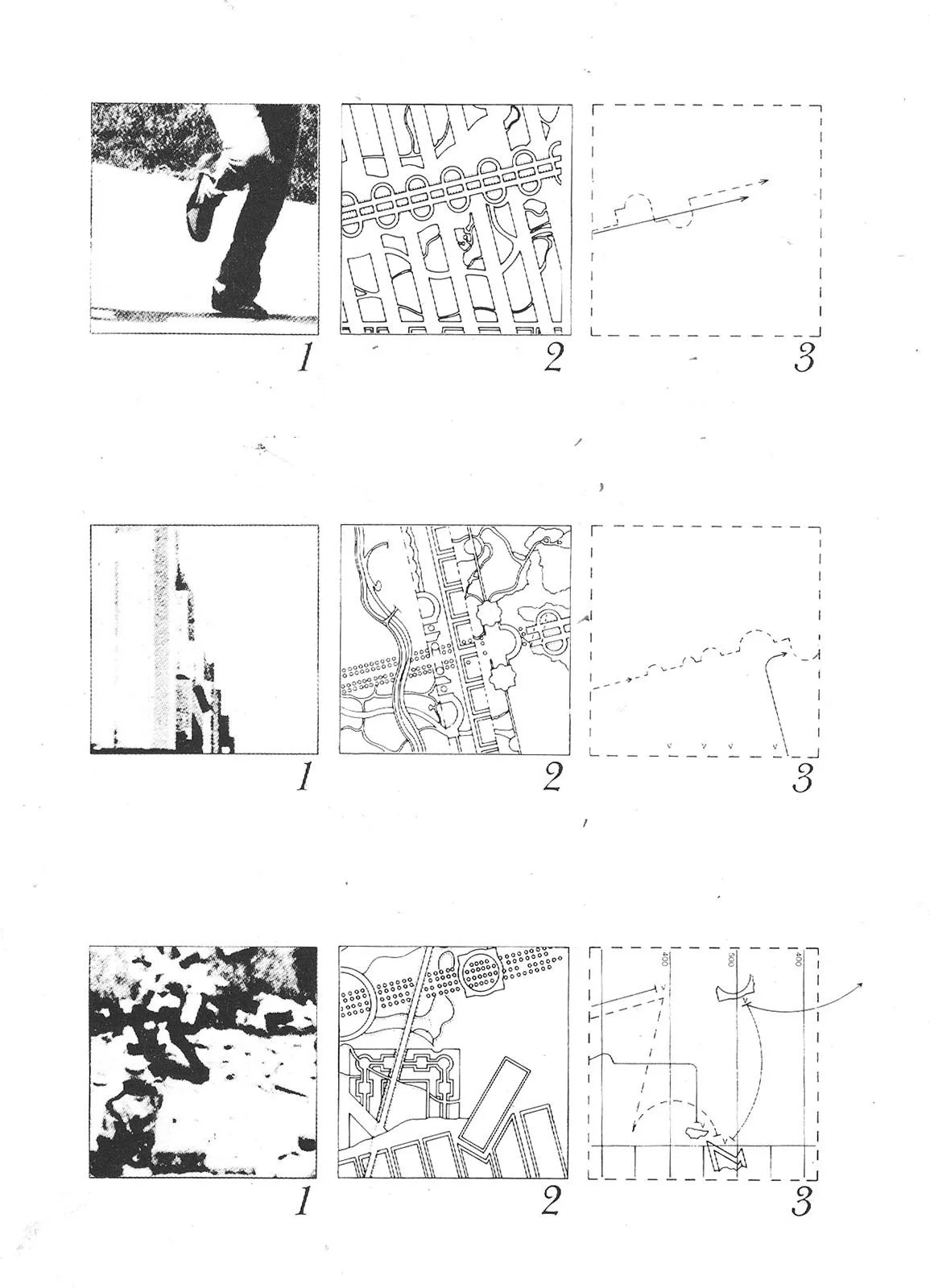

The research then goes immediately into the ‘situationist’ approach of field work of the spaces and archive in sections three and four of this study. There is a deliberate method to simultaneously expose the findings and discuss the spatial theories together. This adoption of theories seeks to form a framework around the evidence, with which to observe the findings from early childhood at a domestic level. The topic of this research is primarily spatial memory and the theories of spatial practice. Space, event and movement of the architect Bernard Tschumi are discussed, along with theories of embodied and evocative memory from writers such as Svetlana Boym, Marc Trieb, Pallasmaa. J and Gaston Bachelard. The context of the work within the field of spatial production is shown with my own accompanying visual studies – photography, drawings and collage.

The methodology taken for this study is an autoethnography method. Only by direct participation, in the form of fieldwork within the physical spaces, it is believed that any qualitive research can indeed come about.

The attempt to step outside of oneself and look in, to question position, location in life and how your upbringing and early environment shapes the way we are. This has influenced my approach to artistic research and practice, guiding me to this specific time of interest – the time I was born into and leading up to my appearance in the world and childhood. This time aligns with optimistic growth and the promotion of family life in the UK following the aftermath of the second world war, and it is this time that particularly resonates with me.

The autoethnographic approach gives a unique insight into first hand research from the point of view of the artist. Some may argue that this study is only from one person’s point of view and therefore self-indulgent, however, by gathering data on the self (and others in the process).

“that is narratively sound, introspective, and sensitive to cultural diversity and identity.”

“‘I see culture as a product of interactions between self and others in a community of practice. In my thinking, an individual becomes a basic unit of culture. From this individual’s point of view, self is the starting point for cultural acquisition and transmission’. ”

This study, therefore, attempts to highlight the state of a culture from a child’s perspective.

The challenges of ‘insider’ autoethnographic research is appreciated here.

“though often maligned and ridiculed based on its perception as a lazy and narcissistic approach to research, autoethnography remains a valuable and worthwhile research strategy that attempts to qualitatively and reflexively make sense of the self and society in an increasingly uncertain and precarious world”

This auto-ethnographic approach to the research gives the opportunity to study a site specific place and takes embodied knowledge and first hand accounts into consideration. This method is a meaningful approach and brings into question my own perspective and understanding of a past time. Taking the qualitative research method, the participation of reliving and visiting actual physical places now, makes a connection with real lives and the practice interest (the passive research).

The research, therefore, is taken through the lens of the artist’s own personal experiences. Experiences that are rooted in their own social, cultural and historical context. The aim is that the approach values the artist’s own embodied memories to provide a window through which we can begin to feel sensitivity, empathy and appreciation of the diverse cultural backgrounds of others.

The study aims to take the observations and insight of Griffin S&M (2019) who argue that autoethnographic research must be analysed, ethical and theorised.

“to call for a moderate autoethnography, in which the rigour of analytic tradition can be coupled with the creativity of the evocative tradition, to produce an autoethnographic approach that exemplifies the best of both worlds”

The research aims to take this moderate autoethnography approach, which seeks a middle ground between analytic and evocative autoethnographic traditions. The analysis taken by studying the micro – in this case specific significant places and theorise them against the macro – the wider community and world. The study aims to take a rigorous, honest and robust approach to this self reflection and is always continually aware of the lens of others. The research does not seek to just benefit the author, but to hopefully benefit qualitative study generally and to evoke reflection and question pre-conceived attitudes to another person’s first place of home and therefore another’s experiences. The combination of self, space and cultural reflection aims to give a holistic overview of the notion of spatial narrative throughout.

A few visits took place in Oadby, Leicester, over a few weeks during the summer of 2022 and consisted of various methods of documenting and experimentation. There was no particular linear method of study. The project seemed to naturally draw the attention of various sources and conversations.

The project led me to a mixed method of research to gather collectively elements of different perspectives held over a period, to attempt to reach a state of possible definition or redefinition of that time. This collection or a ‘bricollage’ – (S.Turkle 2007) cites the anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, who described bricollage as a way of combining and recombining a closed set of materials to come up with a new idea. My research aims to collect and once again attempt take our imaginations and highlighting elements of a world that evokes not just hope, but belief with progression and transformation.

By the very nature of looking back into the area in question, I had snippets of information from various sources – old photographs, personal objects, some written documents, an architect’s drawing and stories from relatives. Apart from a handful of photographs I have myself, most of the physical data is with my parents in the form of printed and slide photos. My father showed me the slides and we set up the projector.

My father had made a conscious decision to dispose of many slides to condense the collection down – omitting general landscapes with no family shown. Collections and archives that become edited over time change the experience for the participant, as they are passed through generations of family. I had these fresh images in my mind when revisiting the places.

the original working projector (approx. 1955), now a vintage item: Argus 150 watt projector from Hanimex, Sydney, Australia.

The slide projector was then set up at my home and photographs were projected onto a plain wall. The slide projector itself dates from around 1945 - 1955. The slides are a mixture of types, mainly card slides from the 1960s and 70s with a handful of plastic frames and 120mm film glass slides from the 1950s. All the slides are kept in purpose made boxes in date order. The historical photographs projected onto the setting of a house interior in 2022 makes apparent the age of the photograph and therefore the time projected from the past.

Pallasmaa. J (2009) discusses the newness of today has probably been never so obsessive as in today’s cult of spectacular and architectural imagery.

This past is not ‘new’ anymore, but we perhaps only see this as seeming ‘old’ or historical because of the material technological nature of the archive e.g old slides, black and white photographs etc. set against our current ‘newness’. Our world of pop culture, consumerism, surface images and digital interfaces.

These are projections are evocative, stir emotions and give over a sense of nostalgia. Although some of the photographs were taken before I was born, the practice of looking back at family and sites evokes a sense of nostalgia.

“a sentiment of loss and displacement, but is also a romance with one’s own fantasy”

“a cinematic image of nostalgia is a double exposure, or a superimposition if two images – of home and abroad, past and present, dream and everyday life. The moment we try to force it into a single image, it breaks the frame or burns the surface”

This quote from Boym speaks of the tenuous state of the kept historical material and it’s physical presence. Their physical preciousness becomes apparent. Coupled with the present, is this really all about the past ?

“Nostalgia is not always about the past: it can be retrospective but also prospective. Fantasies of the past determined by needs of the present have a direct impact on realities of the future. Consideration of the future makes us take responsibility for our nostalgic tales”

A slide taken of the rear of my first family home, 1963.

We all seem to have a part to play and a responsibility with our recollections – perhaps there is a place for preserving our archives ?

Some of slides of my first house were superimposed over the pinned up architect’s drawing (by my father) of the house for the playroom extension. I felt need to layer events, as in my mind, the memories were a mix of merged images spanning over a few years and all are interrelated. This method relates to disconstruction theory as a way of diagamming the memories as a non linear method.

Creating line drawings from projected slide photographs.

This ‘modern’ estate provided the first spatial narrative and meanings of the world. Taking a variety of images and sources from the present of a past time, this artistic research first begins to visually explore representations of childhood, spaces and events through the lens of spatial theory by various writers and artists.

The mid-century designed and built suburb community of Oadby is an example of ‘modern’ domestic architecture and the political ideologies of the time. An example of a modern estate like many others built around the UK at that time in the late 1950s/1960s, the purpose was to house the growing population and workforce of Leicester.

Increasing affluence in the 1950s facilitated mass consumption of home appliances, entertainment systems (televisions, record players, radios) and predominantly car ownership. New housing in Oadby during the 1950s and 60s responded to the changing needs of the working people. New housing was built along the lines of current thinking with neighbourhood planning, providing all the local facilities for the housing – schools, parks, local shops along with a good connection to the urban city of Leicester for commuters.

Built by a Leicester house builder, George Calverley & Sons Contractors, the first section of housing on the Brocks Hill estate was built in the late 1950s. Subsequent development of housing by other developers continued during the 1960s to create a large residential area adjoining Oadby town. Calverley undertook an extensive study of the American home building industry to formulate a contemporary style.

Typical house type for a detached property in the sales brochure

“It is in our homes that higher living standards are first reflected. In America no one pretends there is a maid in the background, houses are geared for comfortable living with easiest possible running”

The field work for this research was to travel to my childhood area of my first house (ages 0 – 5) on the Brocks Hill Estate. It is here that the discovery of past events, combined with physical places and fleeting memories can realise a new picture. By placing my own body within the real spaces of my memory, a true phenomenological experience can be achieved. This at the same time brings about the veil or lens through which I certainly and perhaps other members of my family view the world. This hopefully will give a greater more visual understanding of our situation in the world.

The research takes four specific places - I concentrated solely revisiting places I remembered – the house and the road, the local park, the infant school and the local shops.

By taking using an analogue method of camera photography the experiment was to mix a subsequent future history from my childhood time with then future technology. The camera, a Canon AE-1, having the already loaded black and white film, I took photographs from the inside of a mini, which was owned and driven by sister Helen.

I chose the places where I had my first memories but then found the memories triggered more memories, combined with some anecdotal information from my sister, I did at times feel I was transported back to that time.

HOME AND THE ROAD

Bernard Tschumi’s practice, teachings and theories cannot be underestimated in the field of spatial practice. Born in 1944, Tschumi is a French/Swiss national and studied Architecture in Paris. An architect, writer, educator and theorist he is known for his theories concerning deconstructivism. As part of this research study, it was interesting to discover that during the early 1970s Tschumi was captivated by the theories of Henri Lefebvre’s distinction between the perceived, the conceived and the lived space as developed in Lefebvre’s ‘The Production of Space’

“I don’t believe there’s a cause and effect relationship between a function and a type of space - but very much how they bounce against one another, how the action and spaces come to play, interact, reinforce or contradict one anothe.”

He further describes his work as a ‘set of disjunctions among use, form and social values’ (B.Tschumi 1994).

Bernard devised new spatial structures from intersections of simultaneous spaces, events and movement. Although conventionally architectural methods are used to devise just new spaces, Tschumi explains

“In architecture, concepts can either precede or follow projects or buildings. In other words, a theoretical concept may be either applied to a project or derived from it”

This study then, forms a concept of a childhood with the retrospective - taking observations derived or following a set of spaces and events, simultaneously, from the past.

The method explored extensively by the architect Bernard Tschumi can be applied to the surbuban spatial studies as a reflective method as part of this study.

These concepts of disjunction cannot be seen without reflecting on how our memories seem to recall events and spaces simultaneously - events/movement & spacial experience. The collage technique combines the 1980’s film camera with photographs of the present (in monochrome), the mini from the 1980’s (evocative of the 1960s) and the original slide photographs of the house from 1963 (in colour).

Collage of outline drawing and film photos on water slide transfer on aluminium sheet backing. 2022.

I have particular memories of the event where I would be walking up the hill of the road from the bottom on the left hand side, as this was the side for my former house. It was a re-creation of an event – a cycle or walk up the road I grew up on., which satisfied the inquisitive.

I photographed her mini car on the road I grew up on, the pavement and the views from the mini going up the road.

Treib.M (2009) states that unlike writing, our built world may choose not too engage communication or memory as it’s primary vocation, yet it records and transmits history nonetheless.

“that our built environment functions literally as a text or a narrative .... architecture serves as grand mnemonic devices that record and transmit vital aspects of culture and history”

Collage of waterslides - event, movement and space. 2022.

“..along with the entire corpus of literature and the arts, landscapes and buildings constitute the most important externalization of human memory”

The house and the road are recalled together. Although I have no memory of passing from one to the other, I have clear memories of events occurring within the house, at the front of the house and along the pavement. In the 1960s is was perfectly acceptable for young children to play in their front gardens and driveways. Young babies would be left in prams to sleep in the warm summer weather on front gardens. Short bike rides were taken down and up the pavement either on my own or more likely with my brother.

Taken for granted, embodied memories or things we feel we already know sub-consciously become apparent and highlight our current status in the world.

Early memories are rarely precise and complete visual recollections. Pallasmaa (2009) describes that we internalize our experiences as lived situational, multi-sensory images and they are fused with our body experience.

“ruins and eroded settings have an especially evocative and emotional power, they force us to reminisce and imagine. Incompleteness and fragmentation possess a special evocative power”

Johnson-Schlee (2022) describes the home as..’like dreams, is made from residue, familiar objects, bits and pieces, the detritus of life: these are the things we assemble around us to create our fantasy environment’.

“We shape our homes, yet the symbols and images with which we build them are already set: it takes strength to break apart their solid foundations”

The built environment preserves the course of time, making it visible. Buildings also contain and project memories. They too stimulate and inspire us to reminisce and imagine

Pallasmaa describes ‘one who cannot remember can hardly imagine because memory is the soil of imagination. Memory is also the ground of self-identity: we are what we remember’ Pallasmaa (2009)

Snapshots of Episode 1: “The Park”

Tschumi. B

“Tschumi believes that Architecture is more than just form-related, rather, it is hugely related to events, the dynamic definition of Architecture. Bernard Tschumi tried to redefine the typical concept of architecture in all of his projects. Tschumi’s works highly show and prove his theory especially when associating it with “The Manhanttan Transcpits”. These transcripts are made up of four series of drawings that push this theory extremely further to the edge into an Architecture of the event and effect”

Using a technique of collage, fragments of reality are dispersed with dreams generated from memories from the autoethnographic research.

Bernard Tschumi’s theoretical perspective is relevant today when we reflect on ways the urban and the domestic dwelling is re-imagined following the covid -19 pandemic.

The reality of our lives being spent more in the home, is that our imaginations are tested and the opportunity to explore memories and dreams is brought to the forefront.

Ashtree Road, Oadby. 2022. Film photo.

Ashtree Road, Oadby, film photo. 2022. The pavement was the most poignant memory.

Ashtree Road driveway & front garden. 1969. It was considered fine to play out the front of the house and leave the baby in a pram unattended.

Ashtree Road, Oadby. film photo 2022.

Extracting top film of photograph using waterslide paper

Collage and acrylic paint: memories of the mini interior driving into the ‘future’

Movement, space and event. Photoshop collage. 2022.

Collage and paint: the future driving into the past

By looking again at the old photographs, people, the objects, events and spaces and then visiting the changed or sometimes here the not so changed environment today, the spaces seem structured by memories and the recollection of intentions in those spaces. Sometimes the difference between the memory and the feeling, thought or intention is confusing and it is hard to know in the mind what is real and imagined.

The acts of memorizing and dreaming are interrelated. The house shelters day dreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace’ (Bachelard 1954).

The landscape and architecture of the house and the road, with little unchanged – cars spaces now dominate the front once front garden areas, evoke the feelings of home, family, safety, nourishment and love. Johnson-Schlee (2022) describes the home as..’like dreams, is made from residue, familiar objects, bits and pieces, the detritus of life: these are the things we assemble around us to create our fantasy environment’.

Pallasmaa. J (2009) states that ‘we are taught to think of memory as a cerebral capacity, but the act of memory engages our entire boby’

The area then was a type of enclave in comparison to the inner city of Leicester environment, it still retains some of the style and character of this time. Over 50 years later, obvious changes have occurred with individualistic styling of house exteriors, extensions, car ownership and the diversity of the population.

THE PARK

My sister is three years younger than me and doesn’t remember life in Oadby, but she offered insight into areas remembered from subsequent visits to the areas, when we went back to visit as older children. Helen remembered how the entrance of the park used to be and I then identified through her insight how this had been entrance developed over time. This then brought back thoughts and memories that were a lot deeper in my subconsciousness, to the forefront of my mind.

The same area of park in 1966 and 2022

Entrance to Rosemead Park, just along from the local shops. 2022.

Pallasmaa describes ‘one who cannot remember can hardly imagine because memory is the soil of imagination. Memory is also the ground of self-identity: we are what we remember’

THE SHOPS

Early memories are of travelling in the back seat of my mum’s mini. Remembering the views out of the window in certain specific locations – waiting in the car outside the local shops and driving onto the road I lived. . The ground, the pavement outside the local shops was important as a visual connection to childhood but also a bodily connection with walking across them again. The built environment preserves the course of time, making it visible. Buildings also contain and project memories. They too stimulate and inspire us to reminisce and imagine

Film photograph from back seat of mini looking at the local shops. A vivid memory from childhood. What we can’t see but can feel from early childhood is the anticipation felt whilst waiting for my mother to come back out of the shops.

The shops of all the spaces revisited have changed the most to me. The building for the row of shops is still there but the external surfaces are poorly maintained. The paint is flaking off the expressive spans of concrete that support the continuous canopy to the shop fronts. Life on the estate is clearly reflected in the diversity and use of the local shops. This area seems to evoke stronger feelings of nostalgia as I can see more change and therefore loss. I am fully aware that I haven’t lost anything - it’s all a conscious mental state with which I have control over.

The built environment provides us with a narrative or as Pallasmaa quotes the philospher Karston harries..’an illusion of meaning’

Rosemead Drive local shops

Oadby town centre shopping

Oadby Town 2022. Perhaps a deliberate policy ? but the original shopping centre in Oadby town, built in the 1960s still remains as well as the local shops building on Rosemead Drive.

The paving slabs of the local shops

The ‘loss’ is an illusion, like a haunting image of a life from the past. It’s a feeling of the disappearance of the sense of a bolder and braver new world, since the neighbourhood was created in response new beginnings. A sense of order has gone, the environment is a now real representation of today’s life against the backdrop of a lost world. The two seems at odds, but that is only my perception. Pallasmaa explains that ‘we judge past cultures through the evidence provided by architectural structures they have produced. Building project epic narratives’. (Pallasmaa 2009). I know that this is my narrative and it would be completely different to someone else. The views I see today tell me the history of time in the microcosmic world of my childhood environment.

THE SCHOOL

The school run on foot was re-created from the house/road to the infant school. This was completely planted at the back of mind and I had no recollection of the short journey on foot I used to make with my brother. Taking this journey again, the memories came back, and certain viewpoints were brought back to me clearly.

The journey to school which would have been on foot was re-traced. The last time I had been this way was when I was aged around 5/6 years old.

I always felt that I had completely imagined (or dreamed) this journey but after visiting the journey again, my memory were true. I was transported back to the moments I took walking from my home to the school and back again at the end of the school day. Was this a phenomenological event ? Am I an adult with a child’s vision ?

Gaston Bachelard’s 1958 book ‘The poetics of Space’ takes a completely different view of spatial practice by valuing images over ideas. Taylor (2021) states that ‘Bachleard takes various images conjured by poetry and literature as his primary phenomenological “documents” of study’

The poetics of Space is a phenomenological interrogation into the meaning of spaces which preoccupy poetry taking the intimate spaces of a house as the phenomenological object.

“In the book, he guides us through an actual or imagined home (your choice), its comforts and mysteries, assembled and brought into focus, in a place and at a time undefined except by the limits of our own daydreams, longings and memories – those inner landscapes from which, he said, new worlds can be made.”

“[A] phenomenology of the imagination cannot be content with a reduction which would make the image a subordinate means of expression: it demands, on the contrary, that images be lived directly, that they be taken as sudden events in life. When the image is new, the world is new”

By living the spaces directly, I knew that my childhood experience would affect my experience of the present. The present moment walking again along the route to school. The past to me is part of my present and cannot be shaken off. I was that child again. Perhaps I was ‘dematurizing’ myself as Bachelard describes below. We can begin to understand the link between memory and dreaming, and distortions that take place through our lives as our imaginations take a lead.

“Philosophy makes us ripen quickly, crystallizes us into a state of maturity. How, then, without de-philosophizing ourselves, may we hope to experience the shocks that being receives from new images, shocks that are always the phenomena of youthful being? When we are at an age to imagine, we cannot say why or how we imagine. Then, when we could say how we imagine, we cease to imagine. Therefore, we must dematurize ourselves”

Brocks Hill primary School Entrance

“What Bachelard means is that memories of the house and its various parts are not something remembered but rather something which is entwined with the present, a part of our ongoing current experience. Bachelard writes about the desire to stop time. The way to transcend history, to produce that space which suspends time, is through imaging and hallucination. Unretrievable history is fossilized, memories stand, they do not move, and therefore for Bachelard it is space, not time, which invokes memories”

“Bachelard adds the physical dimension, arguing that our house is engraved into our flesh. The body it better in preserving detailed memories than the mind is. Other memories are harder to trace and these can be revealed only by means of the poetic image”

The research started with the photographic collection of slides and prints from early childhood. I viewed slides too of my parents and family before I was born. Looking back is fascinating to me and informs me about my own identity and background. These fresh images I stored and carried with me to the spaces and places of childhood. The role and input of family members giving knowledge and insight into events and places provided an additional layer of recalling and were essential to the study.

By the recalling of memories around the home – the park, the local shops and the school, I began to resonate with the writings of the various chosen authors. I could begin to see links with their theories, insights and views alongside my experiences going back to collections and retracing my first home and its neighbourhood. The experience of revisiting the road and the home was considered through the theory of Bernard Tschumi, a retrospective layering of space and the events that took place with the memories. Events and rituals that occurred within the home and along the road are merged within the mind. Site, movement and evocative places are interrelated.

The embodied experience as a young child is shaped by the conceived lived intentions of the urban designers and the codes of behaviour expected in family life on the ‘modern’ estate. The rituals and events of those days are stored within all our senses. I am conscious that this remembering and embodied experiences within us, in our bodies are carried through into our daily life. I become aware of the spatial narratives that have shaped me to who I am. The writings of Treib, Pallasmaa, Bachelard and Taylor informed my analysis here with the recalling of memories. By unpicking even just a little of the past, we can become more curious of how our imaginations work and of the lives and imaginations of others.

By looking into specific places from the past in a community in Britain and recalling our memories, we perhaps can form new ways of seeing – knowledge base or bias we need to extract pertinent questions at the same time, to test the conditions going forwards. This proposition may give us new or important insights into the issues of today and attitudes we take for granted. Today’s young speak of fear of bringing up a child in today’s world of a climate emergency, war and cost of living crisis.

There were fears in the post war period, in the context of the Cold war and the ever present threat of war by division. The period of the study late 1960s/ early 1970s, is set against the political and economic back drop of Great Britain. From growth and progression in the 1950s/1960s, with a renewed sense of hope, new beginnings, space travel, to 1972 when the country was in economic decline with strikes, discontent and angst . Can we attempt to bring back those feelings of hope now ? against a backdrop of uncertainty, divisions and ‘non-truths’ on the 2020s.

Taylor (2021) cites Bachelard with regard to the Covid lockdown and states that the book gives us some crucial tools to help cope with combating a sense of stasis whilst being trapped in the places we reside.

The research was definitely about a journey of self-discovery, searching for my own perspective and its roots, but I hoped that taking myself as a sample or example, readers can begin to think the connection of their first home and culture, and the influences in the way we view the world now. Of course, I realise, not everyone wishes to bring up memories, as past lives can contain trauma and pain, it not for everyone. However, I do think by reading about others and naturally inquisitive, we can achieve a sense of perspective of our own lives. Hopefully the outcome will be the desire to nurture and embrace past lives with compassion and thoughtfulness, as a way to start to make sense of our present day lives and situation. By producing new images amd linking memories with spatial theory during my self-referential investigations, I hope to have made a contribution to approaches in an autoethnography research area.

Finally to conclude, Pierre Nora is quoted as this perhaps clearly expresses the requirement or need to recall memories (if we can and wish too) and it’s attachment to history

“What we call memory today is therefore not memory but already history. The so-called rekindling of memory is actually its final flicker as it is consumed by history’s flames. The need for memory is a need for history”

Bibliography

Bachelard, G., (2014). The poetics of space. Penguin.

Boym, S., (2008). The future of nostalgia. Basic books.

Burgin. V (1996) In / Different Spaces – Place and Memory in Visual Culture. University of California Press

Callahan, S., (2022). Art+ Archive: Understanding the archival turn in contemporary art. Manchester University Press

Chang. H (2016) Autoethnography as Method. Routledge

Freud. S. (1919) The Uncanny. Haughton.H. Introduction (2003) Penguin Group. pp.vii-Lx.

Farr.I ed. (2012) Memory – Documents of Contemporary Art. Whitechapel gallery and MIT Press.

Gray, C. and Malins, J. (2017). Visualizing research: A guide to the research process in art and design. Routledge, Abingdon and New York.

Pallasmaa. J (2009) Space, Place, Memory and Imagination: The Temporal Dimension of Existential Space. In: Treib, M. ed. (2009). Spatial recall: Memory in architecture and landscape. Routledge.pp.16-41

Treib, M. ed. (2009). Spatial recall: Memory in architecture and landscape. Routledge.

Tschumi, B. (1994) Architecture and Disjunction. MIT Press.

Tschumi, B.(1994). The Manhattan Transcripts. Academy Edition

Tschumi, B (1990). Questions of Space. Architectural Association Publications

Turkle, S. ed., (2011). Evocative objects: Things we think with. MIT press.Introduction: the things that matter. pp.3-10

Wills.D.(1980) Oadby 1880-1980. Oadby Local History Society

Articles/papers/Journals/website articles

Callahan.S. (2017) Depletion of Identity, Productive Uncertainty, and Radical Archiving: New Research on the Archival Turn, Konsthistorisk tidskrift/Journal of Art History, 86:4, 330-338, DOI: 10.1080/00233609.2016.1273970

Charitonidou, M., 2020. Simultaneously Space and Event: Bernard Tschumi’s Conception of Architecture. ARENA Journal of Architectural Research, 5(1), p.5. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ajar.250

https://ajar.arena-architecture.eu/articles/10.5334/ajar.250/

Accessed 25-08-22

Cieraad. I. (2010) Homes from Home: Memories and Projections, Home Cultures, 7:1, 85-102, DOI: 10.2752/175174210X12591523182788

Accessed 14-06-22

Dwyer C. & Davies G. (2010) Qualitative methods III: animating archives, artful interventions and online environments. London. SAGE Publications

Progress in human geography, 2010-02, Vol.34 (1), p.88-97

Greenhalgh, J.(2016) “Consuming Communities: The Neighbourhood Unit and the Role of Retail Spaces on British Housing Estates, 1944–1958.” Urban History, vol. 43, no. 1, 2016, pp. 158–74. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26398669. Accessed 15 Jun. 2022.

Griffin.S, & N. Griffin (2019). A Millennial Methodology? Autoethnographic Research in Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Punk and Activist Communities [47 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3), Art. 3,

http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3206.

Heersmink, R., 2018. The narrative self, distributed memory, and evocative objects. Philosophical Studies, 175(8), pp.1829-1849.

Janowicz.M. (2022) Kitchen Debate. The Architectural Review 1487, December 21/January 22. PP.6-10

Johnson-Schlee. S (2022) Room of One’s Own. The Architectural Review 1497, December 2022/January 2023. PP.6 – 13.

Wall, Sarah S. (2016). Toward a moderate autoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 15(1), 1-9, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1609406916674966 [Accessed: May 10, 2019].

Taylor.C. (2021) The Poetics of Quarantined Space: Revisiting Bachelard. The Stanford daily

https://stanforddaily.com/2021/01/17/the-poetics-of-quarantined-space-revisiting-bachelard/

(accessed 04/01/23)

Ward.M Thoughts on critics of Critical and Speculative Design at the intersection of critical reflection and pedagogic practice

https://speculativeedu.eu/critical-about-critical-and-speculative-design/

(accessed 23-08-22)

(2011) - Gaston Bachelard – The Poetics of Space: The attic and the basement

Cultural Reader. Article Summaries and Reviews in Cultural Studies

https://culturalstudiesnow.blogspot.com/2011/06/gaston-bachelard-poetics-of-space-attic.html?m=1

Housing the Citizen-Consumer in Post-war Britain: The Parker Morris Report, Affluence and the Even Briefer Life of Social Democracy

https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A3154401/view

(accessed 18-10-22)